Grenada, the “Spice Isle” of the Caribbean, captivates with its aromatic nutmeg plantations, pristine beaches, and a history woven from indigenous roots, colonial struggles, and revolutionary fervor. This small island nation, comprising Grenada, Carriacou, and Petite Martinique, has evolved from a volcanic formation to a vibrant independent state. Delve into its past to understand how spices, slavery, and sovereignty shaped its identity.

Geological Origins and Indigenous Inhabitants

Formed by underwater volcanic activity around two million years ago, Grenada’s rugged terrain and fertile soil set the stage for human settlement. The first inhabitants were the Arawak-speaking peoples from South America, arriving around 1000 BCE, followed by the more warlike Caribs (Kalinago) by 1400 CE. These indigenous groups lived in harmony with the land, fishing, farming cassava, and crafting pottery. Christopher Columbus sighted the island in 1498 during his third voyage, naming it “Concepción,” though it retained its Carib name “Camerhougue” until Spanish sailors rechristened it after Granada.

European contact brought devastation: diseases and conflicts decimated the Caribs. By the early 1600s, British attempts at settlement failed due to fierce resistance, but the French succeeded in 1650, establishing a colony after purchasing land from a Carib chief. Skirmishes persisted, culminating in the tragic 1654 leap of Caribs from Sauteurs cliff to escape French forces.

Colonial Era French and British Rule

French rule transformed Grenada into a sugar powerhouse. Plantations proliferated, importing enslaved Africans to toil under brutal conditions. By 1700, the population included 3,000 slaves and 500 French settlers. Nutmeg, introduced later, became a staple, earning Grenada its spice moniker. Control oscillated between France and Britain during the 18th century’s Seven Years’ War and American Revolution. Britain gained permanent control in 1783 via the Treaty of Versailles.

Under British administration, slavery persisted until emancipation in 1834, though “apprenticeship” delayed true freedom until 1838. Freed slaves faced economic hardships, leading to indentured labor from India. Fort George, built by the French in 1705 and renamed by the British, stands as a colonial relic overlooking St. George’s harbor, symbolizing this turbulent period.

Path to Independence and the Gairy Era

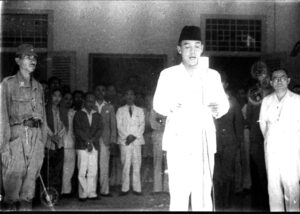

Grenada became a British Crown Colony in 1877, part of the Windward Islands until 1958, then joining the short-lived West Indies Federation. Full internal autonomy came in 1967. Eric Gairy, a trade unionist, rose to power, becoming premier and later prime minister upon independence on February 7, 1974. His rule was marred by corruption, repression via the “Mongoose Gang,” and eccentricities like UFO interests.

Gairy’s authoritarianism sparked opposition, leading to the formation of the New Jewel Movement (NJM) in 1973, blending Marxism and black power ideals.

The Revolutionary Period and U.S. Intervention

On March 13, 1979, the NJM, led by Maurice Bishop, staged a bloodless coup, establishing the People’s Revolutionary Government (PRG). Bishop’s administration focused on education, healthcare, and infrastructure, forging ties with Cuba and the Soviet Union. Cuban aid built Point Salines Airport, later renamed Maurice Bishop International.

Internal strife emerged: hardliners like Bernard Coard deposed Bishop in October 1983, leading to his execution amid public unrest. This chaos prompted Operation Urgent Fury on October 25, 1983—a U.S.-led invasion citing threats to American medical students and regional stability. The intervention, involving 7,000 troops, ousted the regime but drew international criticism.

Post-Invasion Recovery and Democratic Era

After the invasion, a U.S.-backed interim government restored order, leading to elections in 1984 won by Herbert Blaize’s New National Party. Democracy stabilized, though economic challenges persisted. Hurricanes Ivan (2004) and Emily (2005) devastated agriculture, but recovery showcased resilience.

Today, Grenada’s economy relies on tourism, spices (producing 40% of global nutmeg), and offshore banking. Cultural festivals like Carnival blend African, French, and British influences, with oil down (a one-pot stew) epitomizing local cuisine.

Modern Challenges and Cultural Heritage

Grenada faces climate change, with rising seas threatening coastlines, and youth emigration. Yet, its UNESCO-listed underwater sculpture park and biodiverse rainforests attract eco-tourists. The 50th independence anniversary in 2024 highlighted progress, from Olympic achievements to sustainable development.

Grenada’s Enduring Spirit

Grenada’s history reflects Caribbean resilience: from indigenous resistance to revolutionary zeal. Its spices perfume the air, while forts and plantations narrate tales of struggle and triumph. Visiting Grenada means immersing in a living history, where every nutmeg pod and calypso beat echoes the past.